Soul Origin's NEW Baguette Deli Range

Soul Origin launches their new Baguette Deli Range. 3 delectable baguettes to choose from.

Soul Origin's NEW Baguette Deli Range

Soul Origin launches their new Baguette Deli Range. 3 delectable baguettes to choose from.

Just Cuts: OUR CURRENT OBSESSION - THE BUTTERFLY STYLE CUT

We are in LOVE with this latest trend ... come and see why!

Beauty & Health

Become Invigorated With The New Mint Verbena

Introducing Mint Verbena; a refreshing new fragrance.

Beauty & Health

A New Spa-Like Experience With Whipped Shower Cream

Introducing L'Occitane's New Almond Whipped Shower Cream.

Prioritise Your Eye Health with OPSM

It’s important to remember that diabetes can not only affect your general health but can have implications on your eye health as well.

OPSM are committed to helping you take care of your eyes. Book a comprehensive eye test in store so the Optometrists can detect and monitor any issues impacting your eye health.

This Diabetes Awareness Week, be sure to get your vision checked.

Experience a World of Desserts at Koko Black

Get ready to take your tastebuds on a journey around the world.

Koko Black has whisked up a new range of desserts, with favourite flavours afar, and a dollop of magic on the side.

From Europe to the US, we’ve re-imagined classics from French pâtissières and Italian trattorias to Middle Eastern Spice Markets and Brooklyn bakeries, and added a Koko Black chocolate twist.

Upgrade your tastebuds to first class and discover a new world of Dessert Bars and Dessert Bites at Koko Black today.

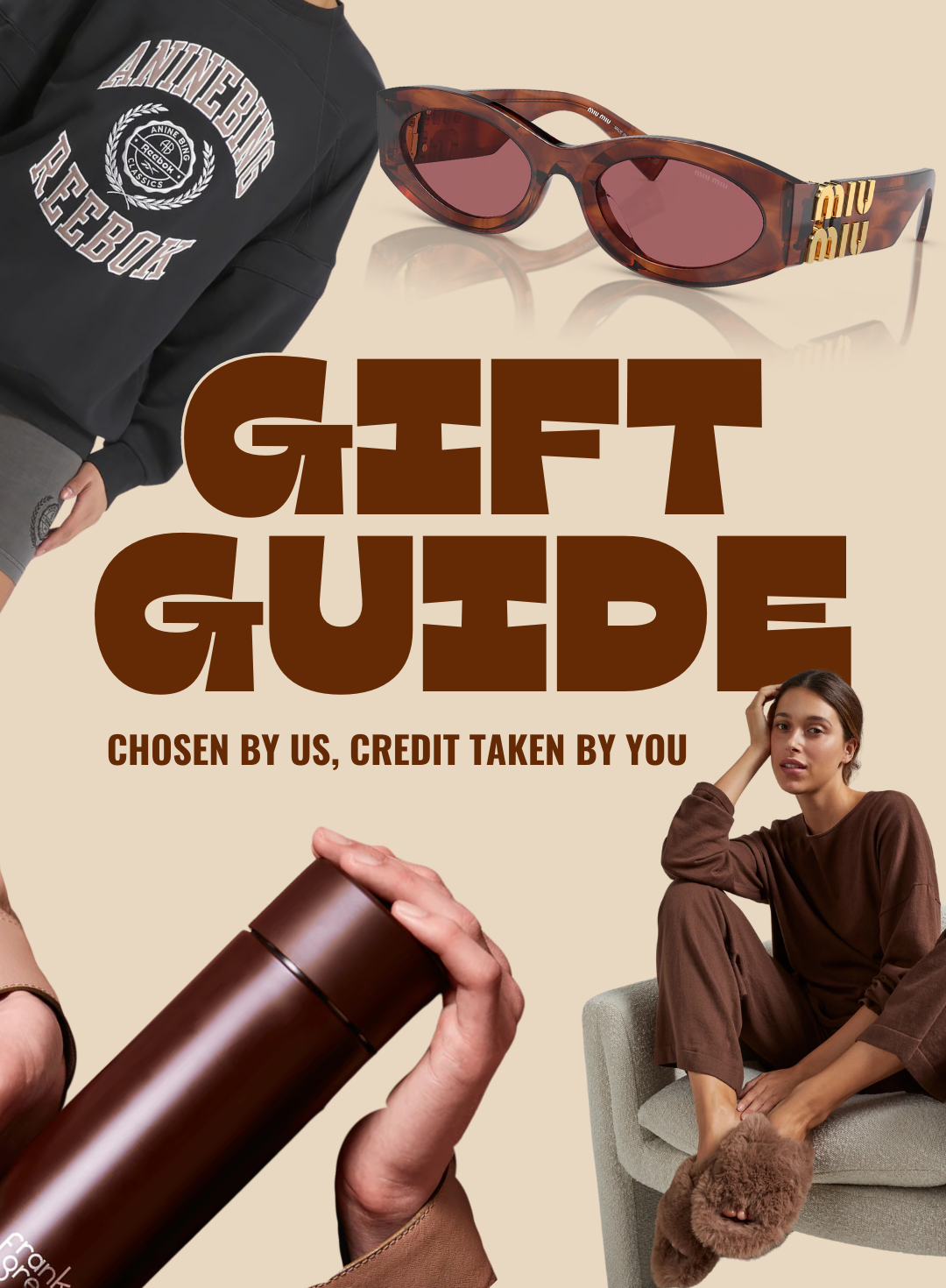

FASHION

LSKD: Introducing the dream fabric

Introducing CloudFLX.

Designed for all day travel and your morning stretches, CloudFLX is a unique synergy of performance and comfort over 12 months in the making.

Built with multi-directional stretch and moisture wicking properties, CloudFLX is ready to stretch and flex with you.

With a buttery smooth hand feel and a light and airy on-body feel for unrestricted movement, this is where performance meets comfort.

Available in jogger and shorts in both mens and womens fits.

Get the dream fabric today in store at LSKD.

Health & Wellbeing

Trust Your Teeth Whitening to a Dentist

At MC Dental we're making it easier for you to discover if professional teeth whitening is suitable for your teeth. You can book a complimentary 15 minute teeth whitening consult to learn more about whitening options, costs and your suitability.

Read our article to find out more about teeth whitening options at the dentist.

*Available with participating dentists. See website or Reception for details.

FOOD

Krispy Kreme New Cheesecake Range

Indulge in our new Cheesecake Doughnuts 🤤 Choose from 🍓Strawberry, 🍫Choc or 💛New York Cheesecake! It's a limited-time treat you don't want to miss

FASHION

Dazzling new Swarovski eyewear at Sunglass Hut

Swarovski unveils its dazzling new eyewear collection.

Recipes

Air Fryer Pork Belly

This delicious and sticky Air Fryer Pork Belly is quick and easy. This hearty winter meal serves a family of 4 and is ready in under 30 minutes!

Recipes

Zucchini Enchilada Roll Ups

If you’re looking for a healthy, low carb, meat free recipe, then look no further. These quick and easy Zucchini Roll Ups are the perfect healthy alternative to lasagne.

Recipes

One Pot Marry Me Mushroom Gnocchi

This creamy meatless marry me mushroom gnocchi is the best one pot budget meal you will make this winter. Coming in at under $5 per serve, this 30 minute recipe is the perfect winter warmer. After you try this recipe, you’ll understand how this special marry me sauce gets its name.

Recipes

Big Mac Hot Dogs

These viral Big Mac Hot Dogs come in at less than $5 per serve. Feed the family for less with these quick and easy hot dogs that come to life with the infamous Big Mac sauce!

Recipes

Healthy Sweet Potato Nachos

Enjoy this healthy alternative nachos recipe for under $5 per serve.

Recipes

Hot Honey Dorito Crusted Cheese Toastie

Level up your toastie game with this Hot Honey Dorito Crusted Toastie.

FOOD

Discover the Delicious and Nutritious New Breakfast Range

Enter, the dawn of a new breakfast range, tailored to fit seamlessly into our mornings without skimping on flavour or nutrition. From savoury buns to hearty wraps, there's something for everyone in this gourmet lineup.

Fashion

Tommy Hilfiger: Curated by Sofia Richie Grainge

TOMMY HILFIGER CELEBRATES A CAPSULE CURATED BY SOFIA RICHIE GRAINGE

FOOD

The Pancake Parlour - NEW Winter Menu

New treats await at The Parlour, explore 10 delicious new choices this winter.

Apparel

TOMMY JEANS: REDEFINING THE MODERN DENIM UNIFORM

Tommy Hilfiger announces the launch of the latest TOMMY JEANS collection of denim essentials that form the dress code of the new generation. The campaign portrays Classic American Cool through a TOMMY JEANS lens, spotlighting moments that celebrate the unifying threads of culture and style within a global circle of creatives defining youth culture.

Food

Soup is back!

Discover the delicious flavours of our new soup lineup for 2024, now available in stores! Warm up your day with our comforting options.

FOOD

Savour the season with Soul Origin soup

It’s that time of the year again when the unmistakable aroma of wholesome soups wafts through the air, inviting you to take pause and indulge in a piping-hot bowl of comfort. At Soul Origin, we're not just bringing back the classics; we're introducing a feast of new flavours to warm your body and soul. Our soup season is more than just about taste; it's about a culinary adventure that you can savour with every spoonful.

Beauty

Enhance your lashes with Essential Beauty’s professional tinting and lifting services!

Enhance your lashes with Essential Beauty’s professional tinting and lifting services! Skip the eyelash curler and try a lash lift to give your lashes a curl that really lasts.

Bailey Nelson Strong and Powerful collection

Introducing the Bailey Nelson Strong and Powerful collection designed by one of BN’s oldest and dearest team members, Meg Halfpapp.

Sunglass Hut New collection: Burberry

Cat-eye sunglasses in shiny black acetate, detailed with the Thomas Burberry Monogram plaque.

Discover the new collection at Sunglass Hut.

Fashion

HI BARBIE

We're making all your Barbie-core dreams come true with this very pink shopping list 💕

Fashion

Circular Future with Nique

They've partnered with Rntr. to offer a rental service for your everyday short-term needs.

.png?width=770&quality=50)

-2.jpg?width=770&quality=50)

.png?width=770&quality=50)