-

- Trading hours

- Contact us

- Location & Parking

- Leasing & Media

- Apple Pay

-

Off-peak timePopular arrival times todayTo determine popular times, this graph shows aggregated and anonymised historical visit data.

-

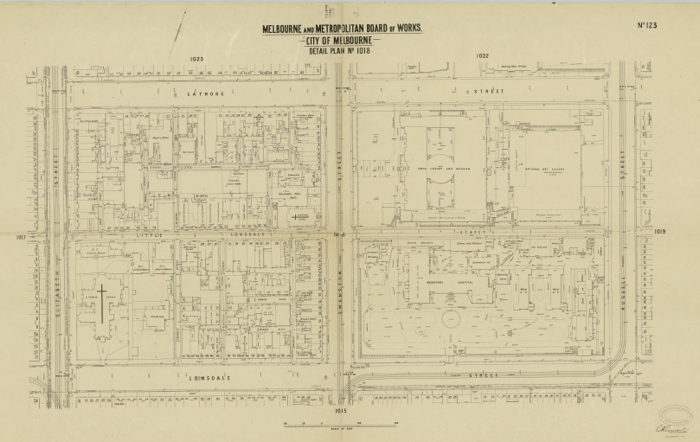

Melbourne’s street names reveal some rad stories. There’s Matthew Flinders, who circumnavigated the country with his cat and was imprisoned by the French for eight years; and there’s David Collins, who camped at Sorrento for three months in 1803 before setting sail for Hobart. With more than 250 streets and lanes on the Hoddle Grid, there are lots stories to uncover—so let’s focus on the blocks of Melbourne Central, featured on this incredible 1885 city map...

SWANSTON STREET

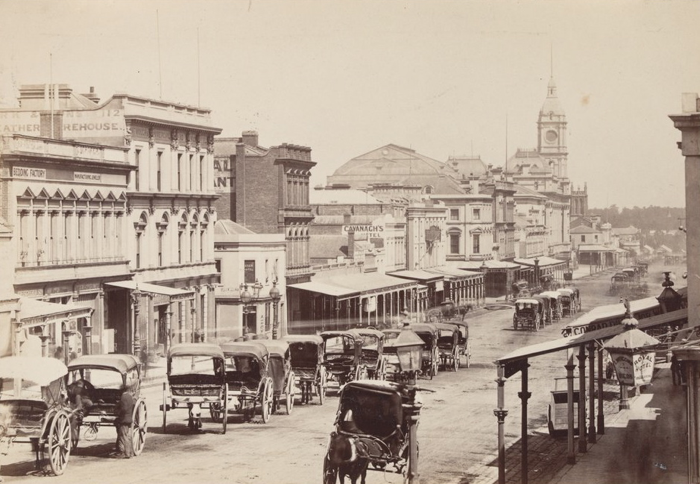

Swanston Street, 1872. Image from the Victorian Patents Office Copyright Collection, State Library of Victoria.

The city’s spine is named for Hobart banker Charles Swanston—a founding member of the Port Phillip Association, who sent explorer John Batman over to the mainland in 1835 to check the place out and persuade the Wurundjeri elders to sell up and move on. Even at the time, the treaty was controversial—but it ultimately led to the founding of a settlement on the Yarra, which became the city of Melbourne.

As director of the Van Diemen’s Land Bank in Hobart, Swanston had introduced the overdraft banking system to Australia in 1834. By 1849 he was more than £100,000 in debt. He took off to America but died at sea in 1850.

LA TROBE STREET

La Trobe Street, Melbourne, 1960s. Photographer unknown.

Out the front of the State Library you can see a life-size bronze statue of Victoria’s first governor, Charles La Trobe.

La Trobe was an unusual choice for a colonial governor. Educated in England and Switzerland, he was a keen mountaineer and a published travel writer—but he had no administrative experience, or even the regimen of army or navy service. In 1832 and ’33 he toured and wrote about the Mississippi and the American prairies, and in 1837 visited the West Indies to report on Indigenous education there. Here was a gentleman, not a general manager.

He did not actively support Separation, but he was not a supplicant to New South Wales—refusing to allow convict ships to land, and sending them on to Sydney. This pleased his colonists but for the most part it seems they hated La Trobe—and actually petitioned London several times to have him removed. He struggled through the discovery of gold and all the challenges it brought, but self-doubt brought him to resign in 1852. In his first speech in Melbourne in 1837, La Trobe had said that it wasn’t wealth or ownership of cows, sheep and land that would secure the colony’s prosperity and happiness, but instead ‘the acquisition of sound moral institutions’. And so it’s Charles La Trobe we must thank for our vast gardens, the library and the University of Melbourne.

La Trobe Street was not part of Melbourne’s original grid, but was added in 1838. Little La Trobe Street was first recorded in 1851.

LITTLE LONSDALE STREET

Little Lonsdale Street, 1950. Image from the State Library of Victoria collections.

William Lonsdale was Melbourne’s first top cop, but Little Lonsdale Street was famous for its bawdy houses. Little Lon’s racing heart was between Spring Street and Exhibition Street, where Madame Brussels and her girls entertained the city’s elite in lavish Marvellous Melbourne style. You can check out the remains of a Little Lon slum street as well as artefacts from archaeological digs at 50 Lonsdale Street.

The stretch of Little Lon between Swanston and Elizabeth was more industrial than naughty—home to an Indian rubber clothing manufacturer, a confectioner, cigarette makers, the St Francis Church School and the Hibernian Hotel. We’ve lost two streets in this block: St Francis Street once ran alongside the church, and Patrick Street connected Little Lonsdale to Lonsdale in the spot that Melbourne Central’s Lonsdale building now sits. The Busy Bee Hotel was here until the early 1960s, and Catholic booksellers have been trading on the strip since at least the 1880s.

Curiously, Little Lonsdale Street is the only little street on the grid that runs in an easterly direction. But it’s only been that way since 1961. Before that (from 1916 onwards) all the little streets ran westerly towards Spencer.

KNOX PLACE

Left: A view of Melbourne Central's surrounding streets and buildings, photographed by Michael Brady on Dale Campisi's Unlocked Tour. Right: Knox Place in 1966. Photograph by K. J. Halla. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Knox Place takes its name from the 1863 John Knox Church at the corner of Swanston and Little Lonsdale streets. Named for the founder of Presbyterianism, the church was designed by Charles Webb (the same architect who created the Royal Arcade and South Melbourne Town Hall). Inside, the stained-glass windows are definitely worth a look. They were designed by North Melbourne stained-glass makers Ferguson & Urie.

Knox Place was also the business address of Coop’s Shot Factory and Lead Manufacturers. In its heyday, the 13-storey Shot Tower—now protected by Melbourne Central’s Glass Cone—produced six tonnes of lead shot every week. The molten metal was simply poured through a colander at the top of the tower, forming spheres as it fell 50 metres into a tub of water below.

Head to the front of Ugg House at the base of the Shot Tower and you’re standing on what was once Little Church Street. In 19th century Melbourne, one side of this street was taken up entirely by the lead works. Opposite, you’d find a mix of sheds and outhouses, and the entry to Darcy Alley leading out to La Trobe Street. These days you can look 20 storeys straight up from this spot to the tip of the Glass Cone.

MENZIES ALLEY

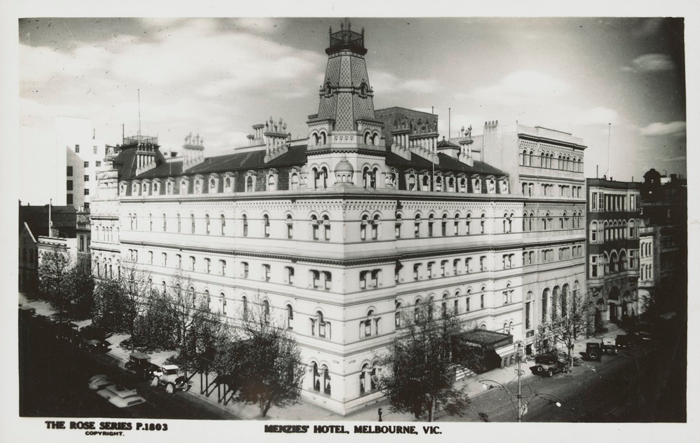

Rose Stereograph Co postcard showing the Menzies Hotel, Melbourne, 1935. Image from the Shirley Jones collection of Victorian postcards, State Library of Victoria.

Running through to Elizabeth Street, the Menzies Alley we know today takes its name from Menzies Street, which ran off Little Church Street and provided a back entry to the Menzies Family Hotel on La Trobe Street.

Archibald Menzies built his hotel in 1853 from trees felled on site. A travel brochure of the time called it a place where “wealth, rank and title mingled with the arts, sciences and learned professions”. It was so reputable that even the fellas from the gold escort, who transported gold from the diggings to the treasury, made it their unofficial headquarters.

It began when Archibald himself found gold in Gippsland, and he and his wife Catherine decided to build a new hotel. They were thinking big, and hired Reed & Barnes—the architects of the State Library and the Town Hall (and, later, the Exhibition Buildings). From 1867 until the modern era, the Menzies Hotel at the corner of William and Bourke streets was considered the finest hotel in town. It’s long gone now, but the tastes live on. Thunder Road brewery’s ‘Terry’s Ale’ is made to a recipe first used in 1870s Melbourne, and no doubt enjoyed at the Menzies.

ELIZABETH STREET

Interior of Finlay Bros. Motor Cycles, Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, ca. 1930-ca. 1950. Image from the Harold Paynting collection, State Library of Victoria.

Elizabeth Street is probably named for New South Wales Governor Richard Bourke’s wife, but Robert Hoddle allegedly claimed to have named it after Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen. Whatever its provenance, the section of Elizabeth Street between La Trobe and Lonsdale streets has been the centre of motorcycle culture in Melbourne since the late 1890s, when bicycles were first fitted with engines.

The Harley Davidson Motorcycle Club had its first meeting around the corner at the Ritz Cafe in 1924, where it was duly noted that Triumph riders were also welcome. Modak has been on Elizabeth Street since the 1930s, and Mars Leathers since 1946. Motorcycle shops lined both sides of the street until the 1970s and—along with the Great Ocean Road and Phillip Island racetrack—this block is still a must-do for visiting bike enthusiasts.

DREWERY LANE

Drewery Lane, photographed between 1950 and 1980. Image from the Mark Strizic collection of photographic negatives, State Library of Victoria.

Historians disagree about the name’s origins, but we know that this small street was changed from Brewery Lane to Drewery Lane in 1872. Several pubs backed on to the lane, and there were also rubber manufacturers, clothiers and a billiards maker.

SNIDERS LANE

Sister Bella bar, Sniders Lane, 2014.

Sniders Lane was originally named for ‘Sniders and Abrahams, Manufacturing Tobacconists’, who made cigars and cigarettes here from 1870. They built the art nouveau Dovers Building at the corner of Drewery and Sniders lanes for their factory in 1910, which was among the first reinforced concrete buildings in the world. They became one of the country’s leading cigarette makers, famous for their collector cards of footy players and Victoria Cross soldiers. Sister Bella bar is now at the end of the lane, and some may remember its predecessor Double-O—one of the city’s very first hidden laneway bars.

Dale Campisi will be leading a special 'laneway edition' of his popular Unlocked Tours at Melbourne Central during One Day Shopping Festival on Wednesday 20 May. Places are strictly limited! Book here!

Tags

Tue - 10am - 7pm

Wed - 10am - 7pm

Thu - 10am - 9pm

Fri - 10am - 9pm

Sat - 10am - 7pm

Sun - 10am - 7pm

Melbourne VIC 3000

Join The Conversation