MELBOURNE CENTRAL'S HERITAGE

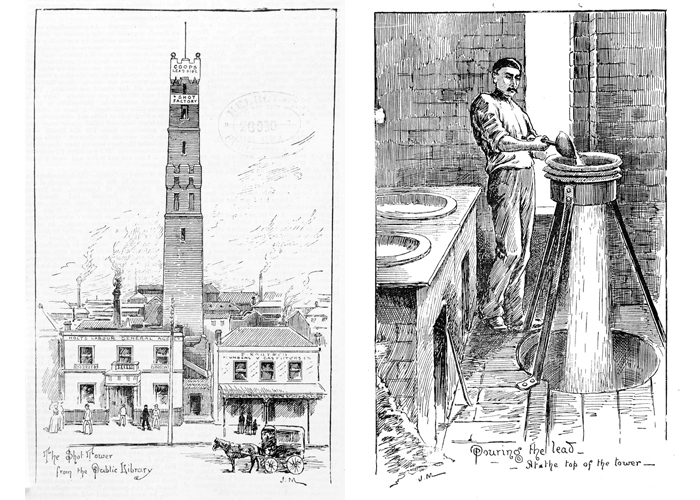

THE COOP’S SHOT TOWER IN 1889

Surely one of the most-Instagrammed buildings in Melbourne, the Coop’s Shot Tower inside Melbourne Central was the tallest building in Melbourne's CBD until the mid-1940s, and has become one of the city’s most enduring landmarks. It's also one of the most significant buildings in Australia’s industrial history.

The Coop’s Shot Tower is one of only three 19th century shot towers remaining in Australia—the oldest (and the only one you can climb) is in Hobart; the tallest is just five kilometres away in Clifton Hill. Thanks to the shopping centre built around it during the 1980s, the Coop’s Shot Tower is the best preserved. Inside the second floor of the tower, Melbourne Central's Shot Tower Museum has the low-down on the history of shot manufacture.

:

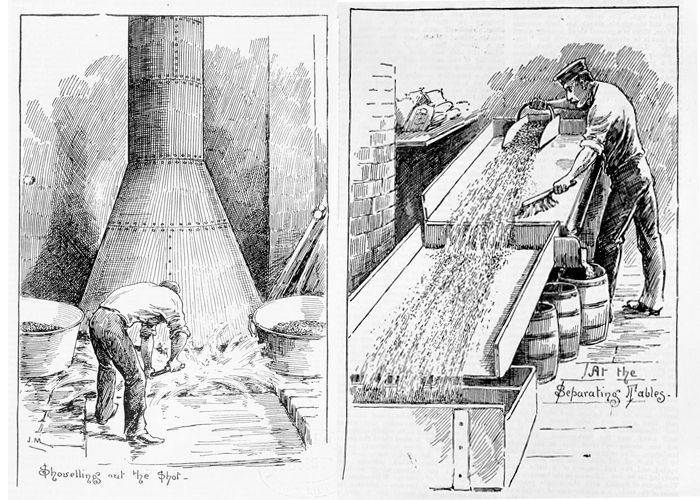

How Shot is Made, prints published in the Illustrated Australian news, 1891. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Shot is made from lead, and is much favoured by small game hunters. All the lead used at the Coop’s Shot Tower came from Port Pirie in South Australia, where it was mined from the ground and carted by train to Melbourne. A typically price-volatile metal, lead was sometimes bought in bulk and stockpiled on the first floor of the buildings that you can see flanking the tower.

How Shot is Made, prints published in the Illustrated Australian news, 1891. Source: State Library of Victoria.

On a shot-making day, the shot maker would load the pig iron (in the form of lead bars) into a bucket on the second floor. He’d then take the 300-odd stairs to the top of the tower, where he would use a pulley to haul the lead to the top. There, he’d fire up a gas ring vat and melt the lead, which boils at a reasonably low 118 degrees Celsius. Then he would ladle the molten lead into a colander and the lead would fall 132 feet into a vat of water on the second floor. By the time it hit the water, the molten lead would have cooled into spheres of lead shot, which were then shovelled into rolling machine dryers (each punched with holes for auto-sizing) on its way to being packed into bags, ready for despatch and use in shotguns, on scales, in pin ball machines and puzzle games—and even as ships’ ballast.

Some 25 million individual shot pellets could be produced every hour, but the Coop family didn’t just make shot here. They made all manner of lead products—from old-fashioned weights to nails and solder, as well as the stair grips for Melbourne’s trams and all of the lead pipe that was used to encase the city’s first electricity system.

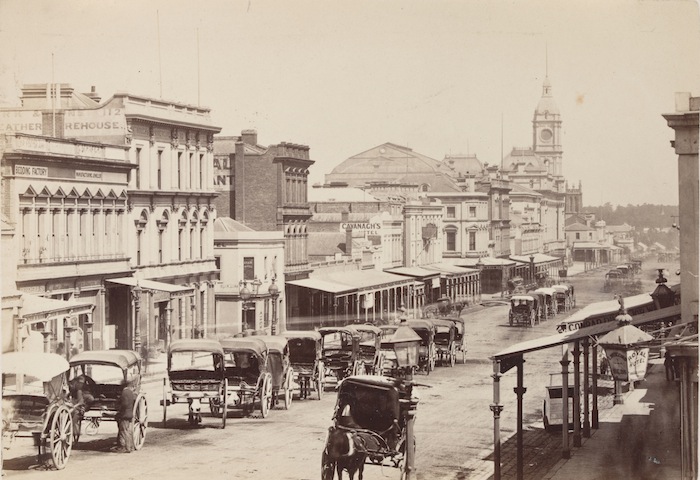

View of Melbourne Looking East, 1860. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Yes, the Coops were a busy family—and their plumbing supplies business and shot tower was a family-run business from the day James Coop the elder stepped off the boat in 1855. At the time, Melbourne was gripped by gold fever. The population had ballooned from 30,000 to 130,000 in just five years. James Coop, however, was no fool for gold – he had come to supply the burgeoning colony with that most essential of needs: plumbing.

Initially operating from a little shop on Collins Street adjacent to the Regent Theatre, James Coop's business grew quickly and by 1868 he moved to larger premises on Knox Place in the city’s manufacturing precinct. The network of lanes that once snaked between Swanston and Elizabeth, Lonsdale and La Trobe streets was home to ironmongers, clothiers, cigar makers, hoteliers, tailors, jewellers, confectioners, furniture makers, coach builders and much more besides. This was the working heart of the city at the time, and the Coops were right at the centre of it.

Swanston Street, Melbourne, 1872. Source: State Library of Victoria.

By the 1880s, James’s son Walter was running the show with his own son, also named Walter. The rich gold deposits and the mass immigration that the gold rush inspired had made Melbourne one of the richest cities in the British Empire. The Coops continued to expand their business, this time into shot manufacture. In 1889-90, up went Walter Coop’s shot tower. The castellated red-brick building eventually topped out at 50 metres—several metres above the city’s height limit.

The shot tower was the tallest building in Melbourne, but it was no mere monument. By 1894, the Coops were producing six tonnes of shot per week there. The same year, the family acquired the Clifton Hill shot tower when its operator went out of business. This made Coop’s the largest manufacturer of shot in the southern hemisphere, supplying businesses across Australia and south east Asia.

Credit: Mahood, Thomas O.G. photographer, 1920. Source: State Library of Victoria.

In 1919, Walter II’s sister Ellen assumed control of the business. She was a remarkable woman: there weren’t many women running businesses at the time—let alone in heavy industry. In an incredibly rare instance, she was also awarded custody of her son following divorce from her husband. She ran the business for 20 years, her life cut short when she fell off the back of a tram on Gertrude Street while commuting between the family's two shot towers.

In 1939, James Coop the younger took over the business following his mother’s death. But, as we know, World War II changed the whole world. Metals prices remained ever-volatile while plastic emerged as a cheaper, cleaner and more reliable competitor for many lead products.

Lead was out of fashion: arsenic—a crucial though toxic part of lead manufacturing—could kill you! The Coops shut the city tower in 1961 and, finally, the Clifton Hill tower in 1976.

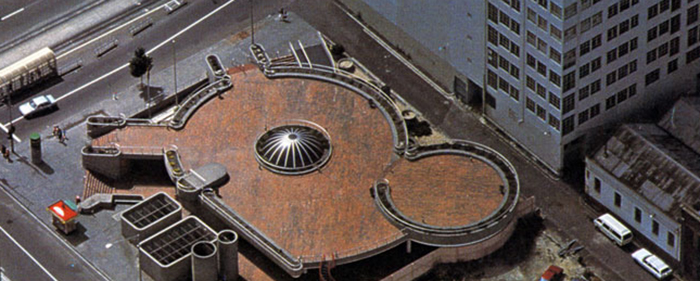

La Trobe Street, Melbourne, 1960s (photographer unknown).

THE COOP’S SHOT TOWER MEETS THE CITY LOOP

During the early 1970s, development in the area surrounding the Coop's Shot Tower was frozen as the city council explored the site’s potential. The tower was heritage listed in the 1970s—recognised as “a unique and peculiar landmark”—and so when the City Loop Authority requisitioned the site, they knew they would have to dig carefully around and underneath the towering structure.

John Gollings Photography, 'The Shot Tower, Pre-Dome'. Source: Heritage Victoria.

Initially every building on the block except the Shot Tower and St Francis’s church was slated for demolition. In the end many were saved, but all shops fronting La Trobe Street had to go in order to construct the new City Loop. Museum Station was the first station to open on the city’s $500 million underground rail loop. It was then known as "Museum" because the Melbourne Museum was located across the road, in the building that now houses the State Library of Victoria.

Construction of Museum Station, 1973. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Passengers emerged from the 29-metre deep station into Queen Elizabeth Plaza—a vast open space on the corner of Swanston and La Trobe streets, right in the middle of the city. The Queen herself opened this plaza, but it would only ever be temporary. The disused shot tower remained—a monument to the city’s industrial past, but now a bit of an albatross around the neck of its future.

Queen Elizabeth Plaza photographed in 1980. Project designer Graeme Butler. Source: Open Buildings.

Having failed to secure an anchor tenant for the site, the state government put the area's development out to public tender in 1983. Japanese firm Kumagai Gumi won the tender and constructed Melbourne Central between 1986 and 1991 at a cost of $1.2 billion. That was big money is those days—but then, at one and a half city blocks, so was the development.

Designed by architect Kisho Kurokawa, Melbourne Central was not a simple development project. The centrepiece was the 55-storey crystalline-form office tower—but the real challenge was preserving the shot tower as required by its heritage listing. Kurokawa’s solution was to marry the old with the new and encase the shot tower in a 20-storey glass cone—the largest of its kind in the world and a counterpoint reference to the State Library’s dome, which is also one of the largest domes of its kind in the world.

Left – Postcard featuring Melbourne Central in the early 1990s. Right – The Coop's Shot Tower, Michael Brady Photography.

In the years leading up to its 1991 opening, Melbourne Central was marketed as “the life of the city". When it first opened to the public, the centre offered 160 specialty shops and 30 cafes and food outlets, with Japanese department store Daimaru taking up six floors. The centre also cleverly included undercover footbridges across Lonsdale and Little Lonsdale streets, linking through to Myer and the city’s traditional retail heart on Bourke Street.

The opening also marked the debut of the now-famous Marionette Watch. In those days the Watch was connected to a giant, 12-foot chain. Today, the cockies and koalas and galahs still dance along to Waltzing Matilda every hour. In 1991, a hot-air balloon and a biplane also dangled in mid-air underneath the cone. Melbourne Central had a giant video screen, murals depicting trades throughout the ages, a rooftop amusement park, and even a serene and surreal butterfly house with its own specially commission hybrid butterfly. The 50-metre tall shot tower took centre stage in what felt a lot like a retail theme park.

Photograph by Rennie Ellis. From the series 'Melbourne Central, under the cone, Daimaru on left'. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Some loved Daimaru. Some hated it. Everyone in Melbourne talked about it. But department store retailing is a difficult business. Myer and David Jones weren’t about to give over any market share to a Japanese interloper. Though they carved out their own niche over a decade of competitive stocktake sales, a faltering Japanese economy forced the closure of Daimaru in 2002. They paid $30 million to abandon their lease, which was not due to expire until 2016.

From the base of the shot tower, you can see the ghost of Daimaru. Look up above the cinema and you’ll spot two escalator landings but no escalators.

Photograph by Rennie Ellis. From the series 'Melbourne Central, under the cone, Daimaru on left'. Source: State Library of Victoria.

THE COOP’S SHOT TOWER TODAY

Following Daimaru’s departure in 2002, Melbourne-based architecture firm Ashton Raggatt MacDougall (ARM) embarked on a $250 million renovation of the centre. Where the first Melbourne Central had followed traditional shopping centre design and created an inward-looking urban space, ARM turned this on its head—opening the centre up to its city location by connecting to the train station below, carving out north-south lanes across the block (as well as new diagonal cut-throughs that Melburnians had always desired), and letting in the natural light.

ARM's famous wooden 'gift box' facade, as it appears today. Photograph by Heather Lighton.

In the process, the Coop's Shot Tower and its flanking buildings were given back their street frontage. Now it's possible to wander from the tower through to Lonsdale Street just as nineteenth century Melburnians once did.

The tower's original address was on a laneway off Knox Place. Located off Little Lonsdale Street (a little way downhill from Swanston Street), Knox Place is still accessible today. Though it's now surrounded by towering buildings, functionally it's pretty much the same as it was during the 1890s—a service and delivery alley. The only difference being that our nineteenth century forebears were carting six tonnes of lead through these tiny alleys every week!

Left – A view of Melbourne Central's surrounding streets and buildings, photographed by Michael Brady on Dale Campisi's history tour. Right – Knox Place in 1966. Photograph by K. J. Halla. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Twenty-five years on from Melbourne Central’s opening, art—rather than industry—lies at the centre's heart. Geoff Hogg’s historic transport mural still adorns the train station’s Elizabeth Street concourse. Knox Lane, which is accessible from Knox Place as well as Swanston Street, has previously been adorned with the artwork of Japanese couple Kami & Sasu. During the 2013 Carbon Festival it was given a new look by husband and wife team Dabs Myla and visiting UK street artist Insa. And the Coop’s Shot Tower itself has been the backdrop for artistic projections during White Night, as well as Melbourne Central's own nightly Shot Tower Heritage Week sound and light show.

The Shot Tower projections at White Night 2014. Photo by Kollide.